Over 100,000 people need organs. Will animal-to-human organ transplants ever work?

The rise of genetically-engineered animals could soon make organ waiting lists a thing of the past. But science has an uphill battle to fight first.

Prior to the year 1920, people diagnosed with diabetes were living on borrowed time. There was no real treatment which could assist their bodies in controlling blood glucose levels — medicine at the time had very little understanding of how the body regulated such things, with most doctors prescribing a very strict diet with minimal carbohydrate intake to prevent dangerous fluctuations. At best, this would buy patients a few extra years, if that. But ultimately, they would succumb to the disease and be remembered as someone whom science could not save.

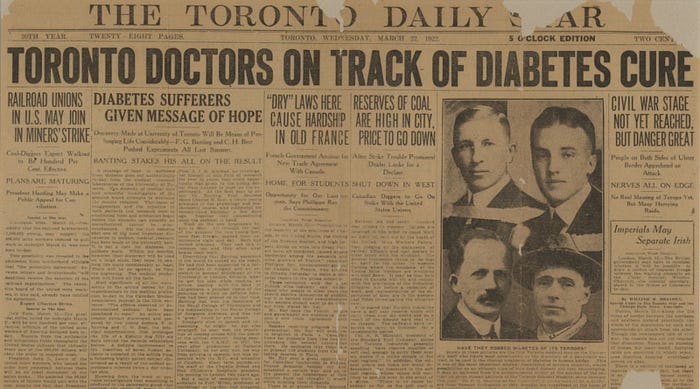

However, a remarkable breakthrough would come in 1921 when a young surgeon name Frederick Banting discovered how to harvest pure insulin from the pancreases of animals. Described by sceptics at the time as nothing more than a “thick, brown muck”, this hormone would go on to save the lives of millions of people and allow them to live much longer, healthier lives. The following year, a more scientifically refined shot bovine insulin was administered to a 14-year-old boy from Toronto. Overnight, his blood sugar levels dropped from hyperglycaemic to near-normal levels — a result which would pave the way for a new era of medicine, one which involved the use of animals to treat human illnesses.

Fast forward one hundred years, and we have come a very long way from the scientifically primal discovery of insulin. As the century went on, skin grafts between species became common — a technique which is much cheaper and more widely available that human skin, and is still in use today. More modernly, and perhaps considered one of the most cutting-edge surgeries available today, humans can now be transplanted with heart valves from pigs — chimerically combining part of an animal organ with their own to create a healthier, more reliable ticker.

The field of animal-to-human transplants — now more commonly known as xenotransplantation, from the Greek xenos- meaning ‘strange’ or ‘foreign’ — has developed remarkably over the years, but there is still one long strived for milestone that remains elusive. One which has played out countless times in newspapers and TV news in the past 50 years, only to end in bitter disappointment. The successful transplantation of an animal organ into a human host.

To this day, there has never been a wholly successful transplant of an animal organ into a human host. Temporary success has been seen on some occasions: a scant number patients have been fortunate enough to live for some months and even return to normal life. But all patients have ultimately died within 9 months of their transplant. Even with current gene editing processes and powerful immunosuppressant drugs, the human body continues to reject donor organs procured from animals. This is a hurdle that scientists all over the world cannot seem to clear, despite the numerous modern techniques and remedies at their disposal. The truth is rejection is so expected — whether it comes in the form of hyperacute, vascular or cellular — that it is a gargantuan task to prevent all forms of it. Even if rejection is avoided, the organ can fail for a plethora of other reasons such as being incapable of matching the synchronous output of a human organ. This makes xenotransplantation the riskiest option for those in need, but often the only one available to them.

There is often broad media interest in such stories of xenotransplantation, and many are penned in an optimistic tone that quietly hopes that this will be the one that works. The most recent case that garnered international attention was that of 57-year-old Maryland resident David Bennett. Suffering from chronic heart failure, Bennett was deemed too ill to receive a human heart, leaving him with no other option than to receive a xenotransplant. “It was either die or do this transplant,” Bennett said, one the day before the surgery. “I want to live. I know it’s a shot in the dark, but it’s my last choice.”

In January 2022, Bennett underwent the transplant at University of Maryland medical centre and it was viewed as a tentative success. His body had not immediately rejected the organ, a heart from a genetically modified pig that had been altered to remove genes which trigger hyper-acute rejection and include human ones to make the organ more palatable for the body to accept. He was well enough to sit up in bed and watch the Super Bowl in February, and the hospital provided regular updates on his condition.

However, two months following the transplant, Bennett’s conditioned worsened and he ultimately died. It was a heartbreaking development in a story that many hoped would be the light-bulb ‘insulin’ moment of the 21st century. On one hand, failure is understandable: transplanting entire organs is far more complex than grafting highly processed tissues like skin. But on the other, it seems impossible with all of the advances modern medicine has made up until this point. These failures no doubt further drive the desire to once and for all solve this scientific Rubik’s cube and save the lives of the millions in need of organs.

However, this is not a new desire — it is one that has persisted throughout the century and has remained unattainable regardless of the adjacent scientific breakthroughs which promise to make things easier. One might even suggest that the desire for possibly merging physical features from various animal species is rooted in mythology: Daedalus and his famously ill-fated son Icarus grafted the feathers of birds onto their arms in order to achieve flight. Even religions like Hinduism often featured deities and avatars which project the duality of man and beast, like the elephant-headed Ganesha. It is with these fusions that humans seek to attain some trait deemed impossible in their human form, like the flight of a bird or the blood-curdling roar of a lion.

While the more fanciful ideas of xenotransplantation have all but dried up, the true goal which has persisted is the desire for new life. It may not be life as a half-man, half-lion, but life simply continuing as a human — only with some assistance from our animal counterparts. It is those who are most critically ill that depend most on this hope for a new lease of life. It is a final chance to be saved from an impending fate, and a choice many take stoically and with a cautious faith that their transplant might be the one that works.

But never once has this promise of longer life been successfully delivered. There have been many near-achievements which have ended in failure; transplants watched with bated breath only to end in despair. The first reported xenotransplantation took place in France in 1905: a child with chronic kidney disease had slices of rabbit kidney inserted into an incision on her own kidney in the hopes of remedying her renal insufficiency. Despite an immediate visible improvement in the patient’s condition, she ultimately died some days later. Various other surgeries followed in Europe using the kidneys of lambs, primates and other animals, but interest eventually waned once the human body’s immunological process of rejection became more understood.

It wouldn’t be until the 1950s with the rise of the first immunosuppressant drugs that the prospect of xenotransplantation seemed like not a too-far-off possibility. Experimental surgeries resumed once again, patients plied with anti-rejection drugs directly after surgery, but the human body once again seemed unable to accommodate the alien organs. Some scientists began attempting to use the organs of chimpanzees, the species most taxonomically similar to humans, with six people receiving chimpanzees kidneys in 1964. Most died in the ninety days following their operation, but one individual, a 23-year-old woman, survived for a remarkable nine months and even returned to her post as a schoolteacher. She eventually was readmitted to hospital with an acute electrolyte imbalance, and ultimately died.

There are also the ethical considerations to contend with — ones which often fuel rifts between various groups of activists as to whether human life is more valuable than that of any other living being. One of they key arguments is that when a human signs up to become an organ donor, they promise one thing that no non-human can ever provide: free and informed consent. Animals are incapable of doing this, so the line becomes blurred on this subject. Some animal rights activists also argue that it is not ethical to kill animals to harvest their organs — particularly those species which are primates (and possibly endangered), like chimpanzees, who also unfortunately happen to be most similar to humans. PETA has described animal-to- human transplants as “unethical, dangerous, and a tremendous waste of resources”, and have remarked that “Animals aren’t tool-sheds to be raided but complex, intelligent beings.”

In more modern examples, the question persists about how ethical it is to fundamentally alter the genetic make-up of an animal to suit the needs of humans. Pigs are the most commonly used animal in current laboratory settings, as their organs grow to a similar size as humans despite various other glaring biological differences. This begs the question, are we tampering with nature too much when we make such drastic moves in the pursuit of scientific breakthrough? This muddying of the water can turn he path ahead into somewhat of a ethical minefield. But most scientists are in agreement that these kind of alterations are necessary to ever overcome the burgeoning organ crisis we now face.

It is difficult to imagine that we as a species are able to genetically clone animals, yet not save our own lives with the heart of a beast. It was in 1969 that Sir Peter Medawar, a British scientist who won the Nobel Prize for medicine in 1960 and is considered the father of transplant immunology, stated, “We should solve the problem [of organ transplantation] by using heterografts [xenografts]… maybe in less than 15 years.” This statement, now over fifty years old, shows the difficulty in predicting the future course of science and that even Nobel Prize winners can get their prophecies wrong.

And as the population of the world has grown, so has the list of people in need of organs. An exponential number of people — over 106,000 in the U.S. alone — are on a waiting list for hearts, livers, kidneys, lungs. Many will die before the reach the top of. Many more won’t even be added to it due to their immediate dire situations; they’ll be long dead before there is even a chance that an organ is offered to them, sometimes many years in the future. This has led some scientists to remark that the future of organ donation balances entirely on the shoulders of xenotransplantation, as demand for human organs far outstrips supply.

The popular almost-success stories, like that of David Bennett, are enough to spur the imagination to visualise a world where terminally ill people can be saved using the kidney of a baboon or the heart of a pig. Despite the operation using the best-possible genetically tailored pig heart, it still failed. But this has instead encouraged instead of disheartened the scientists involved in the procedure.

Dr Muhammad Mohiuddin, the director of the animal-to-human transplant program at the University of Maryland, paid tribute to Bennett: “Mr Bennett was a brave man. Without his contribution, we couldn’t have done this procedure. He was brave enough to donate his body to science and to accept this pig heart, which many would not… this is the first time a pig organ has been transplanted in a human and there are lot of unknowns that we can discover after carefully evaluating the data. A lot of new information will come out that will help the field move forward at a faster pace.”

Looking back at the annals of history, it does take failures like this for breakthroughs to become possible. Scientists now believe they have enough data to convince the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to allow clinical trials with organs that are not immediately fatal if they fail, such as kidneys. Whether these experimental surgeries will be allowed to proceed is yet to be decided, but doctors believe they are essential to finding success in xenotransplanting, reducing organ waiting lists and ultimately saving the lives of millions of people.

How well animal organs work will be for these clinical trials to decide, rather than one-off operations. Many biotech companies are moving cautiously, setting up trials to check whether the organs are safe and effective, first in other animals and then in humans. But for those with failing organs, the only hope for now still remains with the generosity of human donors.

Liked this story? Follow the author on Medium for more content. For comments, corrections and questions, find me on Twitter at @greghill.